Long ago I learned that the best way to tour a city is by bike. A car isolates a tourist from a city, while a bike immerses them in it. A car is a means of racing from tourist destination to tourist destination in as little time as possible, with heavy traffic, protests, and everything else in between being only distractions to avoid. But it is everything between tourist destinations that makes a city what it is, including its people, climate, and culture. A bike contextualizes the city from the perspective of someone living it in.

Much as bicycling lets a tourist appreciate urban context, virtual reality can increase students’ access to the context of what they’re studying. Magazine photos can isolate objects from their surroundings. By contrast, virtual reality apps allow users to explore those surroundings from many angles. For example, the free app Sites in VR provides a view of the West Bank site that houses the Tomb of Moses. One might expect such an important monument as the tomb to be sealed behind glass in a large atrium and surrounded by gold and glitter, yet it is inside a small, closet-like space below an old electric fan. The surroundings seem at variance with the importance of the artifact, which might get you thinking about the region itself. The app lets you do just that, and by looking around the spaces of other monuments your mind starts building an impression of a region with so many religious monuments that they are pressed up against one another. You learn how the area is an intersection of major world religions, crammed into a relatively small space, which helps explain the tensions in the area. All this comes about by adding context to the experience of viewing the artifact via virtual reality.

Pam Snyder and Joshua Wilkins, both instructional designers at Penn State, recently talked about a virtual reality project they were developing about the Roman Colosseum for a history course (Snyder & Wilkins, 2019). A tour of the Colosseum today can easily leave someone with the impression of an enormous ruin; the instructor wanted students to understand how it was an active center of life in Ancient Rome. Stories from the time report how excited people were to attend the games to cheer for their favorite gladiators, much like football fans today. These games supported the “bread and circuses” political philosophy of Rome’s rulers that kept the empire together for so long.

To enrich students’ experience of the Colosseum, the instructional designers first imported Google 360 images of the amphitheater to allow students to look around the present-day structure. To this, they added overlays to demonstrate how it looked and operated in its former glory, where trapdoors led to rooms beneath the floor and pullies hoisted large animals into the middle of the action. It held a remarkable 50,000 people, had a fabric cover over the stands operated by 100 solders, and served as the model for modern arenas. Virtual reality allowed students to witness the Colosseum within the context of Ancient Roman life, and how its design influenced all future arenas.

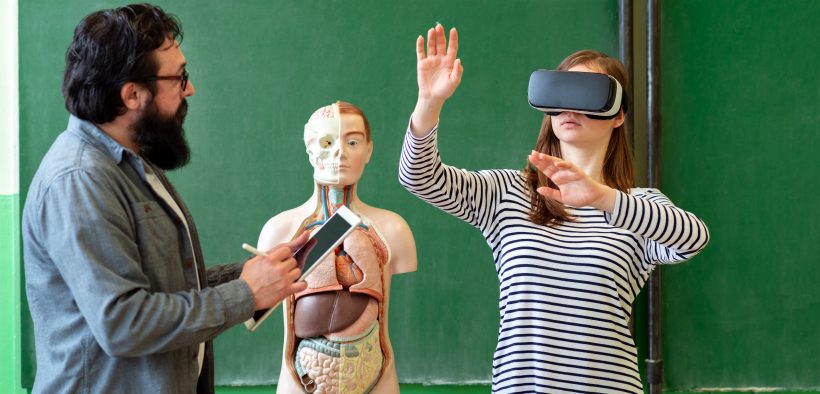

As another example of virtual reality, the Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine at Case Western Reserve University (2016) teamed up with Microsoft to create the HoloLens, which projects a 3-D holograph of a human body into a student’s room. The school did so to address a major discrepancy between anatomical education and surgical practice: the cadavers that medical students conventionally dissect to learn human anatomy differ significantly from what students will encounter as surgeons because human tissue compresses and hardens after death. Using the HoloLens, the student can walk around and explore the projected body, pull out body parts to examine them more closely, spin it around for a different view, and watch how the parts interact with one another. The human body is an integrated system whose parts can be understood only in relation to the whole. Virtual reality brings this context into the picture in a way that lifeless body parts cannot.

Virtual reality in your classroom

Many educators assume that virtual reality requires a $500 pair of VR goggles. But students can view virtual reality content on their smartphones with $5 Google Cardboard viewers. There are also dozens of free VR apps available and hundreds of educational videos to choose from. The most popular ones, such as Sites in VR, NYT VR, Google Expeditions, and the Virtual Reality 360 Video Channel, I profiled in April and December 2016. But a few newer apps merit mention:

- Fantastic Voyage VR tours the human body, letting viewers fly through a beating heart, look around the inside of a brain, and glide among the blood cells coursing through its veins. Viewers not only experience an operating body from the inside but also view it at scales not possible with the naked eye.

- MEL Chemistry VR allows students to see chemical reactions from the inside. Students open one of the many chemistry lessons, which might start in an animated lab and then descend into the inside of a molecule. One about gas pressure starts with a balloon, which the viewer enters and then shrinks to the size of an atom. The viewer then sees how atoms move faster in the gas than in a solid, which creates its temperature. The student has an example of heat and pressure at both a macro and a micro level.

- HP Reveal is an interesting augmented reality app. Augmented reality allows someone to look at their surroundings through their smartphone camera to see not only the real world around them but also a digital overlay. Pokémon Go is an example of augmented reality. HP Reveal allows users to take a picture of an object or place and then connect content, such as a video, to it. When others point their cameras at the same object or scene, the digital content will activate in their views and add to what they see. [Editor’s note (12/28/2021): HP Reveal has been discontinued.]

Augmented reality apps present some exciting possibilities for learning. For instance, students in a history course can create historical tours of their city. Madison, Wisconsin, was a protest center during the Vietnam War. A history instructor at the University of Wisconsin–Madison could assign students to make tours of campus that give the viewer a sense of what it was like to be at those protests. A student can take a photo of Bascom Hill as it appears today and connect it to video footage of protests and National Guard solders firing tear gas. The viewer can thus see the grassy hill from an entirely different perspective.

Similarly, a student in Montgomery, Alabama, could make a tour of landmark civil rights events. The student might film a nondescript street and then connect it with footage of a march on that street. Then a visitor could look down the street and literally see the marchers approaching.

In many ways, higher education itself removes context from learning by transporting the learner from their environment to an artificial location—the campus—to learn a subject and then return to the “real world” afterward. Virtual reality is one way that instructors can reintroduce much of this context to learning.

References

Case Western Reserve University (2016, June 8). Transforming medical education with Microsoft HoloLens [Video file]. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/h4M6BTYRlKQ

Snyder, P., & Wilkins, J (2019, August 7). (Virtual) reality check: How is this supposed to work? Poster session presented at the Distance Teaching & Learning Conference, Madison, WI.