Walk the Talk: Design (and Teach) an Equitable and Inclusive Course

The past 18 months brought us to see systemic challenges and disparities in higher education. The new emphasis on diversity, equity, and inclusion has pushed

A version of this article appears in The Best of the 2021 Teaching Professor Conference (Magna Publications, 2021). Learn about the 2022 conference or submit a proposal here.

The past 18 months brought us to see systemic challenges and disparities in higher education. The new emphasis on diversity, equity, and inclusion has pushed each of us to recognize hidden barriers and inequities that our students have been dealing with all along. In my desire to be a compassionate teacher, I ask myself: What else should I be doing to be "inclusive"?

Let’s take a moment to envision what an equitable and inclusive classroom looks like. As instructors, we see inclusive teaching is to build a welcoming, bias-free classroom climate, incorporate diverse voices into course content, and adopt Universal Design of Learning (UDL) for improved accessibility and different learning needs. At the same time, students perceive an inclusive classroom as a place where they can share different perspectives and express their voices, their diversities are being seen and respected, and they have equal opportunities to succeed.

Though it sounds pretty straightforward, inclusive teaching hasn’t been picked up as widely as we’d hope. Although you may be only partially conscious of your hesitancy, please take a moment to complete this selective checklist of the 20 inclusive teaching strategies. You will be surprised by the degree of inclusive teaching you may already be employing or are only narrowly missing. After all, inclusive teaching is fundamentally good teaching with an intention to remove any potential barriers that will impede student learning and to provide necessary resources to support academic success of all students. It is above and beyond accommodation for students with disabilities or conversations about social justice issues. Many of us who care deeply about students have intuitively adopted some (if not many) teaching practices to support an inclusive classroom without explicitly knowing the impact they have on our students. But there isn’t a one-size-fits-all inclusive teaching checklist for our courses. Each of our classrooms, in fact, is unique on account of our different teaching styles, student populations, and disciplines.

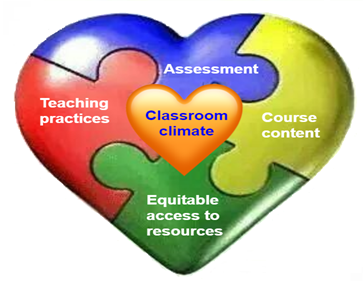

Inclusive teaching is a multifaceted approach. This framework to achieve inclusive teaching is composed of five distinct, yet interconnected themes (Figure 1). With this framework, we can design a custom bundle of inclusive pedagogical practices for our curriculums and classrooms.

Figure 1. A five-theme framework for inclusive teaching

For our students to feel welcomed and safe, we must build a learning community where they can cultivate a sense of belonging by developing meaningful relationships with their instructors and peers. This process begins with a deep understanding of ourselves (self-identity) and the impacts of our actions and words. It is necessary to recognize and admit our implicit biases before we might begin to unlearn them. We need to take the time to get to know our students—from their preferred names and pronouns to their career aspirations. With a self-created survey, we can always gather more personal information in advance of each semester to help craft a desirable classroom climate.

A syllabus with friendly tone and inclusive language (using “we” or “us”) always cultivates a warm atmosphere before students and I even meet. Since I noticed that students are often not aware of my intentions to promote inclusion, I now include a personalized Inclusive Teaching Statement to communicate exactly why, how, and what I am doing to promote diversity, equity, and inclusion in the classroom. An instructor’s positive talk along with constructive praise and meaningful feedback can help students recognize their “abilities” to learn and succeed, particularly for underrepresented students who constantly experience hardship and face challenges (Canning et al., 2019). First-generation students, female students, and students of color often receive less guidance and mentorship than their non-first-gen, male, and White peers. These pep talks and small gestures (micro-affirmations) have a disproportionately affirmative influence in their classroom experience, their motivations to learn, and their persistence and achievement.

To promote social belonging, we can introduce activities that prompt students to know and learn from each other (peer learning). One way I’ve facilitated this is by creating casual chats during what I call “coffee hours” and “lunch hours” (names denoting a laid-back atmosphere) in addition to my “office/student hours,” where my students and I connect and build rapport. I schedule my coffee hours at different times of the day and switch dates occasionally so everyone has a chance to attend.

Sometimes we have students entering our courses with less background knowledge than their peers. This underpreparedness is common for students who attended schools with inadequate resources or are financially disadvantaged, limiting their access to academic opportunities—such as advanced placement courses, boot camps, and summer internships—that are more routine for students from wealthier families. Traditional, lecture-based teaching can favor already privileged students and discriminate against underprepared first-gen and minority students because people learn best when they have a strong foundation to begin with (Paul, 2015). By contrast, a well-structured, active learning course provides interaction, feedback, and support that promotes comprehension, retention, and skill building, particularly for underrepresented student groups (Haak et al., 2011).

One way I assess and intervene in this imbalance in background knowledge is by assigning pre-lecture assignments (with incentives) to activate students’ prior knowledge and prompt them to identify concepts about which they need further clarification. For students who are introverts, are from other countries, or fear or are inexperienced with public speaking, preassigned discussion forums allow them to organize their thoughts and formulate their arguments in advance and establish anticipation for in-class participation. When students are prepared to engage, it facilitates equal opportunity for learning.

With my students coming with a variety of interests, experience, and skill sets, I encourage team collaboration and projects as well as formation of study groups to show how they can learn from one another. Inclusive pedagogical practices are those that promote student engagement and metacognition, embed effective learning skills and study habits into the course structure, and provide peer-learning opportunities. These practices offer underprepared students resources and skills they will need to excel in college, yet they are completely lacking in these students’ prior educational experience due to systemic inequality and disparities.

As a concept, accessibility does not have to be limited to students with accommodation requests but can apply to all students and their learning needs. While adopting UDL is a great way to accommodate these individual learning differences, it may not acknowledge unique student needs that we do not actually see, as students are often resultant (or hesitant) to ask for help. We must make certain that all students have equal access to learning materials, resources, and environments. In recent years, I have adopted free and accessible learning materials and textbooks (open educational resources) for most courses I teach. When I introduce a new educational technology for classroom learning, I prioritize the free version or provide alternatives for students with financial hardship or other concerns. During campus closure due to the COVID-19 pandemic, I sent out a student resource survey to gather information on their access to internet service; electronic devices such as computers, webcams, and printers; and other learning resources necessary for them to succeed in my courses. If not, we worked together to find solutions to ensure adequate access.

Attention challenges are growing in today’s youth. So, I edited my 75-minute lecture recordings into several 10–15-minute-long segments based on topics. These shorter video clips make it easier for students to pause for questions and return to content that they found challenging, and they can be reviewed in chunks that fit students’ overloaded schedules. Adding captions to lecture recordings, in addition to benefiting students with hearing impairments, deepens engagement for international students, non-native English speakers, and students whose home situations aren’t always ideal for learning (i.e., with lots of background noises). I offer multiple assignment formats (i.e., PDFs, Word docs and Google Docs) to avoid compatibility issues and accept alternative formats, such as image files or audio recordings, from students who rely on their phones to complete and submit their assignments. With inclusivity in mind, we can pave an equitable pathway for student learning before they even make the request.

Representation matters! To achieve inclusion, we must broaden the range of voices that students hear and include in our course content experts of all genders, ethnicities, and backgrounds. When teaching biology, I seek stories and images of Asian scientists, Iranian chemists, and women biologists of color and discuss their contributions to our current understanding of biology. I address how the building of scientific knowledge is a collective effort by an international science community. We must design assignments and discussions in a way to include all voices from our students and encourage them to seek culturally diverse resources in their research. Diverse role models not only support diversity in the classroom but also encourage inclusion through our emotions, motivation, and social belonging. We all strive to be better when we feel we belong to and self-identify as part of a profession or community.

In my early teaching career, I mistakenly assumed that all my students knew how to prepare college papers. It wasn’t until I attended a Transparency in Teaching and Learning workshop that I realized how my misperceptions unfairly put already disadvantaged students into an even worse situation! Since then, each of my assignments includes purposes, step-by-step instructions, rubrics, and criteria with examples demonstrating levels of “high quality” as well as opportunities for revisions and peer evaluations. While we worry that our students lack many process skills, such as critical thinking and problem-solving, we also know that we don’t acquire these skills overnight. Students who have not yet been challenged (or taught) cannot automatically jump through the hoop to connect, analyze, and evaluate for further applications on their own. We can provide classroom activities and strategically guide students to consider different perspectives, seek connections between ideas, and learn ways to transfer their learned knowledge and skills to new contexts.

Throughout my education, summative assessments (i.e., exams and quizzes) were the only metrics to determine how good I was at performing in my academic work. While we emphasize that mistakes are part of the learning process, using only summative assessments for student performance sends a contradictory message. Exams and quizzes, which don’t represent the full scope of what students are learning, should not be the only way to track students’ learning performance. In my courses, students are rewarded for their effort, dedication, and thoughtful participation (60 percent of their final grades), which captures and reflects their learning progress. This practice not only steers them away from extrinsic rewards (i.e., grades) but also rekindles their interest in what they are learning.

Students who are underprepared or unfamiliar with academic practices and resources (i.e., first-gen or transfer students) often struggle at the beginning of their academic years. It also takes time for students to become acclimated to an individual instructor’s exam style and format and adjust their study habits when needed. Averaging student performance over time can punish students for these adjustment periods, which diminishes and misrepresents their actual achievement, even if they reached levels of content mastery by the end of the course. Recent discussions about “ungrading” can not only help us to refocus our goals on student learning but also explore fresh ideas for more equitable grading.

I chose a heart puzzle for inclusive teaching because our compassion and care for students form the foundation of this framework. Such an inclusivity mindset echoes the centerpiece of the heart and guides other pieces to fit together as a whole. There is no one way to put these puzzle pieces together. If we pay attention to what our students need the most, each puzzle will reveal itself as a unique assembly that reflects our teaching style, student population, and classroom culture. Let students speak to you, and remember: you are making this puzzle together. We need to give ourselves permission to make small, incremental steps as we seek innovation. Inclusive teaching is a lifelong journey that requires continuous learning, adjusting, and evolving. I hope this framework encourages you to take your first steps toward inclusive teaching—and many more.

Canning, E. A., Muenks, K., Green, D. J., & Murphy, M. C. (2019). STEM faculty who believe ability is fixed have larger racial achievement gaps and inspire less student motivation in their classes. Science Advances, 5(2), eaau4734. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aau4734

Dewsbury, B. M. (2020). Deep teaching in a college STEM classroom. Cultural Studies of Science Education, 15, 169–191. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11422-018-9891-z

Feldman, J. (2019). Beyond standards-based grading: Why equity must be part of grading reform. Phi Delta Kappan, 100(8), 52–55. https://kappanonline.org/standards-based-grading-equity-reform-feldman

Haak, D. C., HilleRisLambers, J., Pitre, E., & Freeman, S. (2011). Increased structure and active learning reduce the achievement gap in introductory biology. Science, 332(6034), 1213–1216. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1204820

Paul, A. M. (2015, September 12). Are college lectures unfair? The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/09/13/opinion/sunday/are-college-lectures-unfair.html

Ching-Yu Huang, PhD, an assistant professor at Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU), has taught a variety of biology courses since 2008. She specializes in educational technology, active learning, peer-learning, and inclusive teaching. She served as a Provost’s Faculty Fellow at VCU’s Center of Teaching and Learning Excellence during 2019–2021.