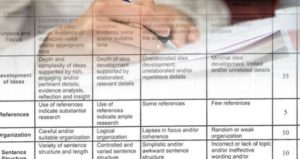

Addressing the Cons of Using Rubrics in Assessment

Proponents of rubrics champion them as a means of ensuring consistency in grading, not only between students within a class but also between instructors teaching the same class. Rubrics, they say, also clarify to students the standards of excellence on which they’re being assessed (Taylor