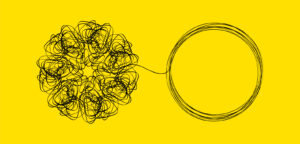

Brainstorming Problems and Their Solutions

Brainstorming is a near ubiquitous means for groups to initiate planning for a project, whether in business or in class. The assumption is that by starting with a blank slate, asking people to throw out ideas without judgement, groups will get a wider range