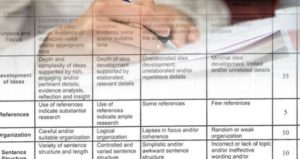

Rubric Options for an Online Class

Athletes are often “graded out” by their coaches after a game, and they always know ahead of time the exact criteria that will be used to grade them. An offensive lineman knows that he will be graded on the number of sacks allowed, missed blocks,