I like to read vintage books on college teaching, ones written before the current profusion of pedagogical research that has occurred since 2000. The classic work (at least for me) is McKeachie’s Teaching Tips, first published in 1953 and now in its 14th edition (McKeachie & Svinicki, 2013). Although it now has many competitors, for decades it was the go-to book on the theory and practice of teaching, and it remains an excellent reference. Lately, I’ve been reading the work of Kenneth Eble, a professor of English at the University of Utah. Eble published prolifically on teaching until his death in 1988. He excelled at weaving together the research at the time with his own reflections into an accessible, useful narrative for new and veteran teachers. As an English professor, he took a more humanistic approach to teaching, but his ideas are quite consistent with current research coming out of my own area of cognitive science. His book, The Aims of Teaching (Eble, 1983), discusses personal characteristics of teachers that affect student learning and motivation and that have nothing to do with the content or organization of the course. For example, he states that teachers “must provide assistance both to overcome the students’ own internal impediments to learning and to increase the willingness of the student to work at this particular kind of learning” (p. 140). Today we talk about those impediments as poor metacognition, ineffective learning strategies, insufficient prior knowledge, and so on. For teachers who believe they need worry only about the accuracy and organization of their presentations, it is a jarring wake-up call.

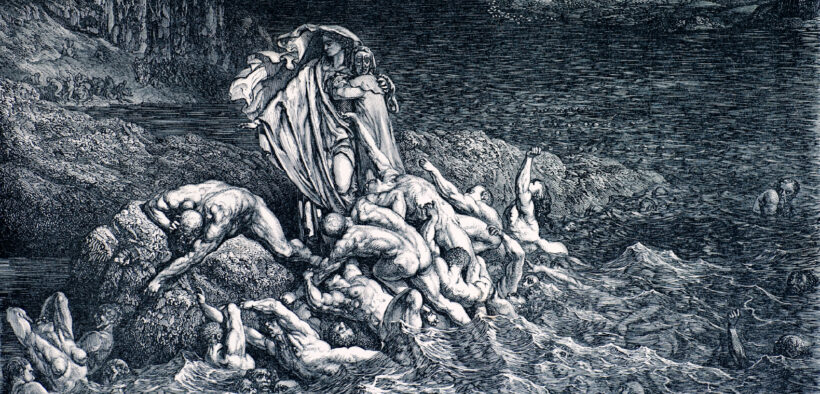

The Seven Deadly Sins of Teaching

Related Articles

I have two loves: teaching and learning. Although I love them for different reasons, I’ve been passionate about...

Active learning is a mostly meaningless educational buzzword. It’s a feel-good, intuitively popular term that indicates concern for...

Perhaps the earliest introduction a student has with a course is the syllabus as it’s generally the first...

Generative AI allows instructors to create interactive, self-directed review activities for their courses. The beauty of these activities...

I’ve often felt that a teacher’s life is suspended, Janus-like, between past experiences and future hopes; it’s only...

I teach first-year writing at a small liberal arts college, and on the first day of class, I...

Proponents of rubrics champion them as a means of ensuring consistency in grading, not only between students within...

One Response

Thank you for such a clearly set out explanation. I have long “felt” this and you have given me words to use.